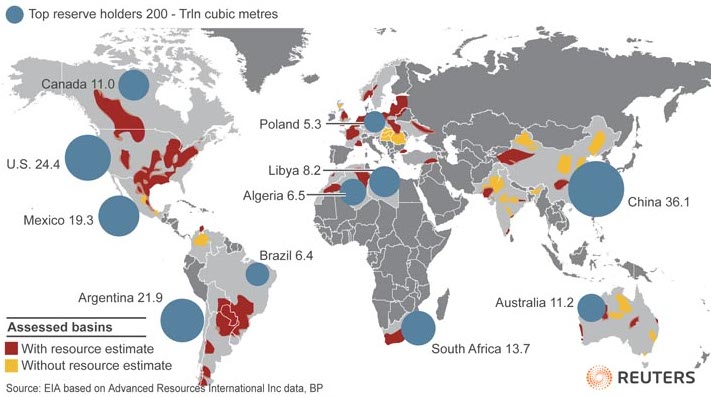

Hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) has represented a major boon for the US economy, producing $36 billion in 2011 and rising year over year. Understandably, other countries have been watching – and some seem determined to join in on leveraging the new technology.

Our previous post, Shale Development Keeps Us Guessing: Who Will Frack Next? PART I, took a look at efforts in China, Argentina, and South Africa. Now we switch our focus to Europe – namely Poland and Russia. (Read about start-up efforts in Colombia, Kazakhstan, India, Israel, and Mexico in our third and final post in this series.)