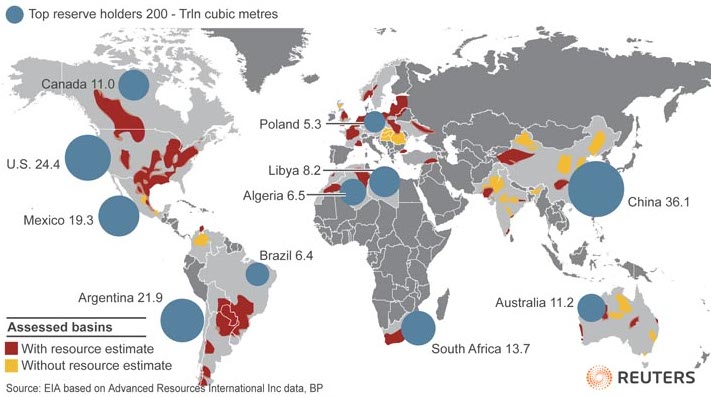

We’ve explored the developments in other necks of the woods, from China, Argentina, and South Africa – who seem close to meaningful shale production – to Poland and Russia – who perhaps have farther to go to achieve measurable shale success. But now let’s ask: Are others ready to join the race?

As it turns out, Mexico, Colombia, and India appear to be pursuing their own shale projects. But like individual shale plays, each of these countries faces its own unique hurdles. The viability of their lofty aspirations remains to be seen.