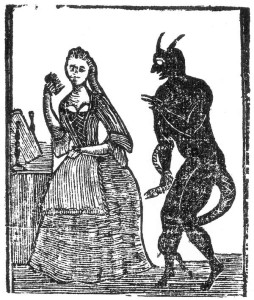

You might call the public debate on fracking “a moral panic.”

When it comes to questions of the environment vs. fossil fuels (especially shale development), New York City, Colorado, California, England, France, Bulgaria, and South Africa are becoming epicenters of public anxiety and panic. Many fear that hydraulic fracturing is an outright threat to the moral, social, and environmental fabric of neighborhoods (a.k.a. “moral panic”). Lawmakers and anti-fracking activists (or “fractivists”), celebrities and shale barons (so-called “frackmasters”), local communities, politicians, and scientists have been debating – sometimes shouting – about the risks and rewards of this comparatively new shale exploration technology and its effects on planet Earth.