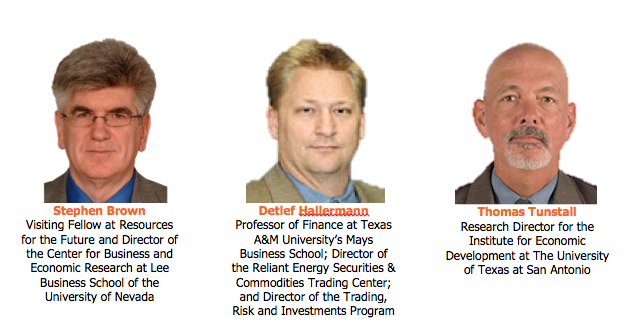

What would the future look like without the crude oil export ban? We spoke with three noted economists who shared their predictions about how lifting the ban would affect consumers, the US economy, and global security – and who might be standing in the way.

Canary: For some historical background: When and why was the export ban first implemented?

Tunstall: It was a result of the Arab Oil Embargo to the US. It was meant to ensure that domestically produced crude oil was used and processed here in the US as a way to augment the shortage from Saudi Arabia and OPEC. For decades, the law didn’t really matter because the US was increasingly importing more and more crude oil because we just weren’t producing as much.