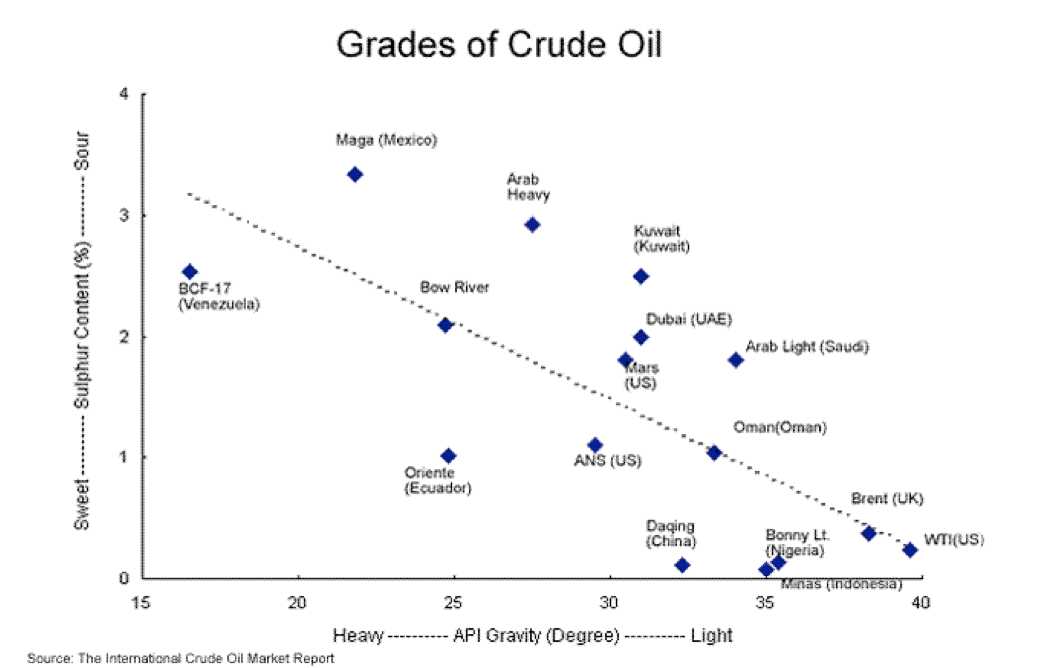

If you’ve ever stared at your local coffee house menu board, completely baffled by the names and choices, then learning about the variety of crude oils extracted from the ground might be an equally mind-boggling experience… only without the caffeine kick afterward.

But understanding how crude oils differ from one another and what kind of refining process is required for each can shed light onto one of the critical issues the oil and gas industry faces today. And that is: Do US refiners have the capacity to take advantage of abundant shale production?