Cast iron is a pretty durable material when it comes to, say, skillets.

But for gas and oil pipelines? As it turns out, not so much.

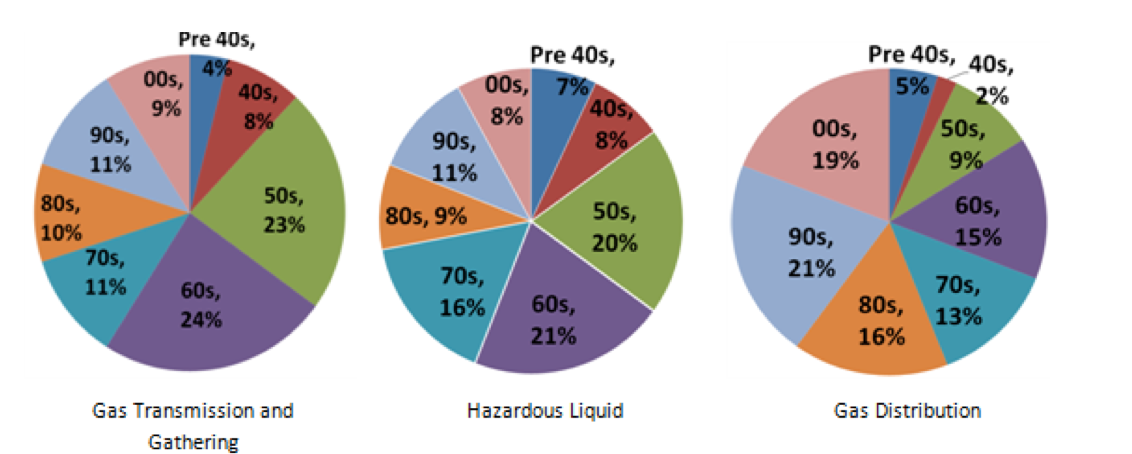

Cast and wrought iron were the metals of choice for pipelines constructed in the US prior to 1940. Even after steel pipelines came into vogue during the post-War heydays of the 1950s and 1960s, cast iron was still being pressed into service in the race to build the high-demand interstate pipeline network.

To suggest that those pipelines have grown old gracefully would be, well, a lie. Consider that even at its best, cast iron is kind of a cranky metal. It’s non-malleable: it can’t be bent, stretched, or hammered into shape. Because it’s brittle, cast iron can crack or break easily, sometimes as a result of ground movement in proximity to buried pipe.