Oil prices haven’t just declined in recent months – they’ve plummeted. It doesn’t matter what news station you watch or what newspaper you read, someone is talking about it.

Oil prices haven’t just declined in recent months – they’ve plummeted. It doesn’t matter what news station you watch or what newspaper you read, someone is talking about it.

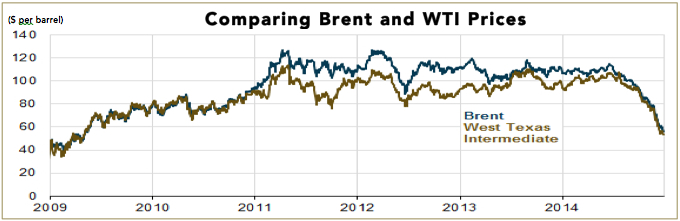

Most of the time, the media outlets reporting on oil prices don’t do a very good job of explaining the current situation. They simply state where the price currently stands in terms of a dollar amount per barrel and move on to their next order of business. This can be very misleading to the average audience because it insinuates that there is one singular benchmark for oil that is used throughout the globe. In reality, however, liquid petroleum is priced differently depending on its region of origin, and knowing why is important to understanding how oil markets across the world operate as a whole.