For decades, petroleum engineers have known of vast quantities of oil trapped under the ground in Colorado’s oil shale rock. And for decades, oil companies have been struggling to find an economically viable way to release that oil from the underground rock.

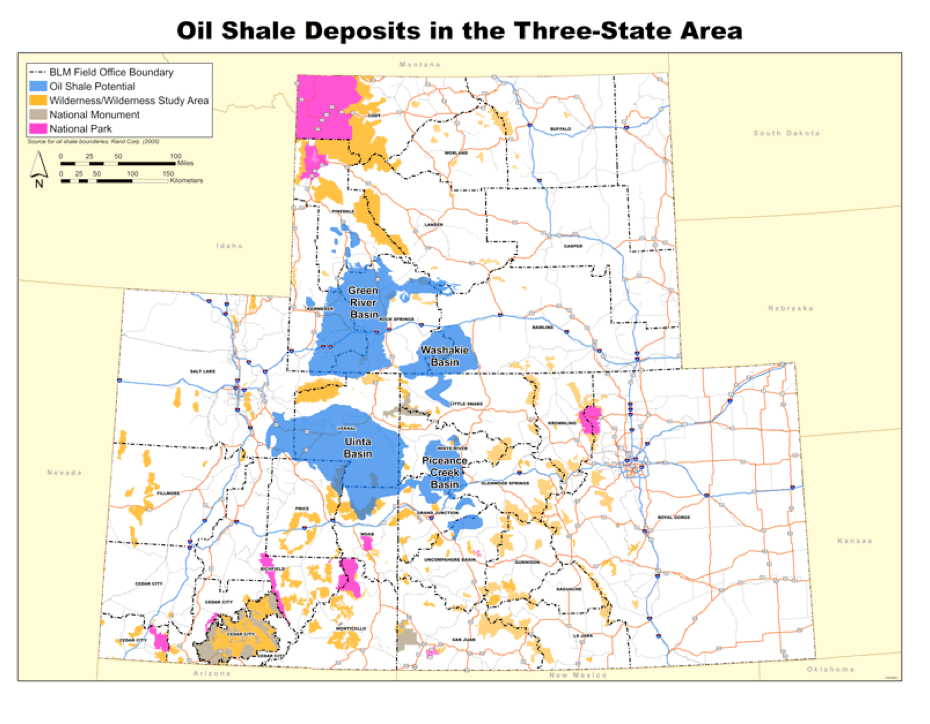

The most abundant oil shale beds in the world lie in the Green River Formation, located along the border of Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah. Expert estimates of the oil contained in the Green River Formation are in the trillions of barrels. Although not all of the oil in this Shale Country area will be recoverable, it’s still estimated that about 800 billion barrels could be extracted – three times as much as Saudi Arabia’s proven reserves and enough to satisfy current US demand for more than a century.