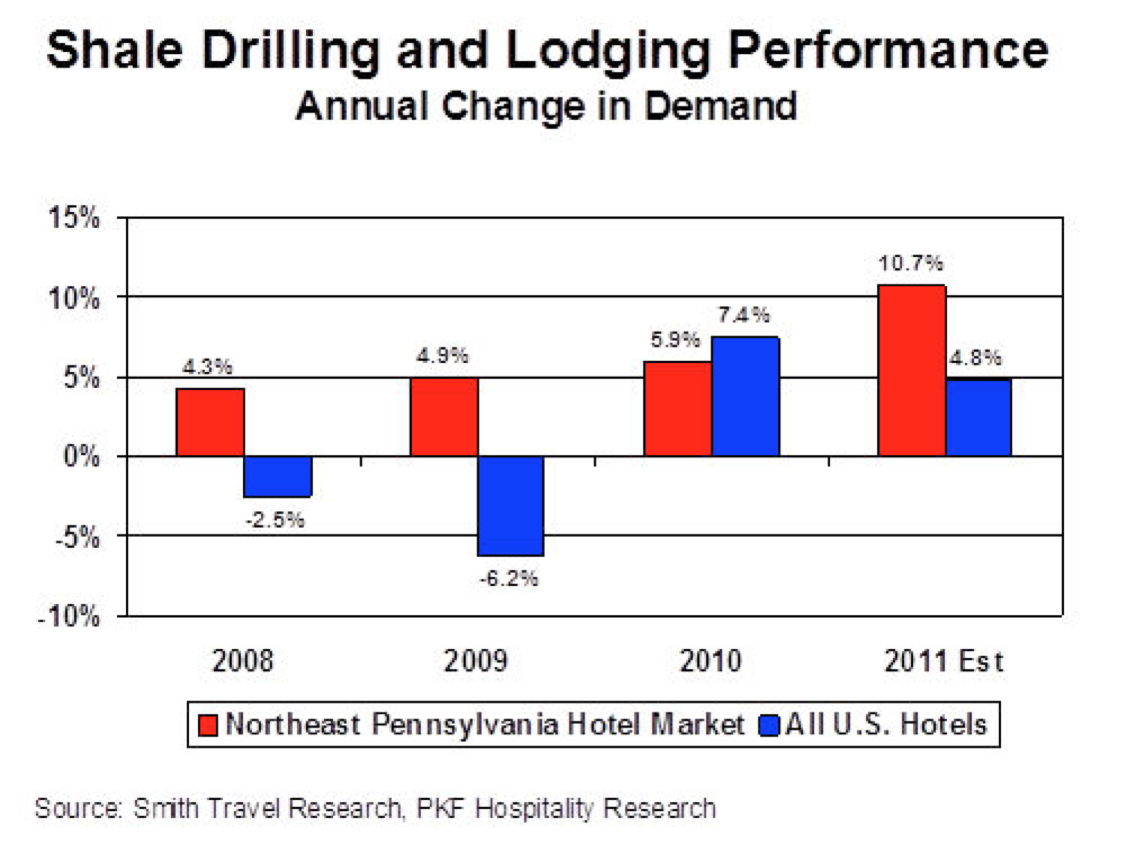

Although experts may have reservations about predicting the longevity of natural gas and oil shale plays, there’s no doubt that the demand for hotel rooms near drilling sites has the hospitality industry convinced of the energy boom’s staying power.

From Marcellus to Bakken to Eagle Ford, neighboring hotels are often overbooked – even occupied beyond capacity – with energy workers, from loggers to lawyers. Major companies rent blocks of rooms for weeks on end, propelling lodging occupancy stats far above the September 2013 nationwide average of 63%. As a result, local economies are growing, and hotel developers are scrambling to build new accommodations.

Higher Occupancy at Higher Room Rates

The 170-room McClure Hotel in Wheeling, West Virginia, tells a typical tale of Marcellus-driven growth. In 2010, occupancy hovered around 40%. Less than 18 months later, the rate was 75%. Some nights, the house is completely full. The property’s general manager attributes the turnaround to one factor: natural gas drilling.