If oil and gas from the domestic shale boom are going to take the US to energy independence, will it be by pipeline, rail, or truck?

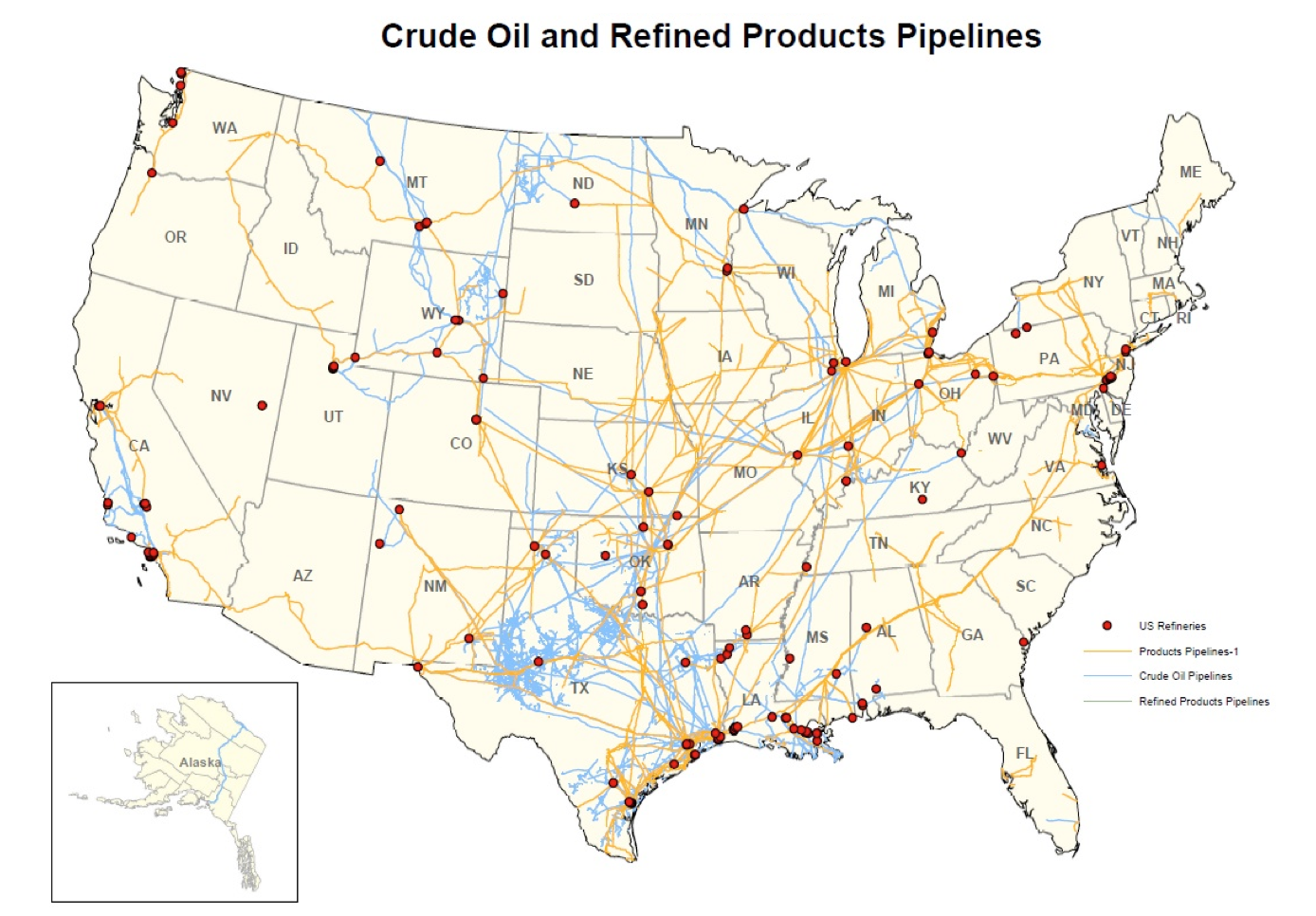

Production and consumption patterns were at the center of the decades-long development of America’s pipeline infrastructure, which actually dates all the way back to before the Civil War – when some pipes were made of wood… admittedly not the best material choice to transport potentially combustible material. The long-distance, large-diameter, steel pipelines that we associate with today’s domestic energy industry were pioneered in the 1940s to meet the rising demand from World War II. During the post-war economic heydays of the 1950s and 1960s, thousands more miles of pipeline were laid, creating the web-like empire of oil and gas now flowing beneath our feet.