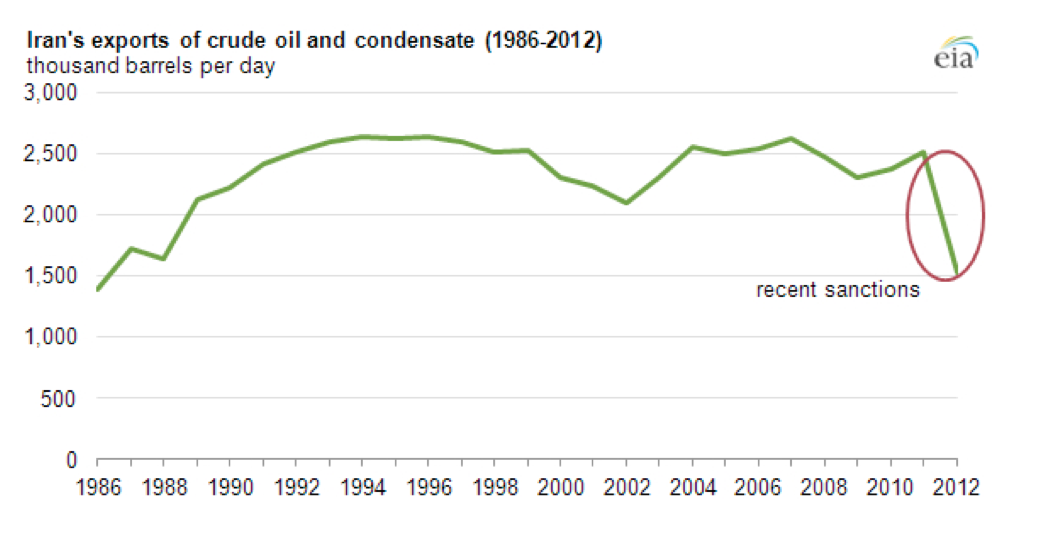

When Iran continued to enrich uranium despite UN Security Council resolutions and sanctions on Iranian exports by the US and EU, it seems that this oil-rich OPEC nation, accustomed to practicing strong-arm tactics in an energy-fueled geopolitical landscape, failed to notice one pretty significant thing: Growing production of US shale resources was lessening America’s dependence on foreign crude. The “radicals” in Tehran hadn’t considered the changing energy picture, said Princeton University fellow and former Iranian ambassador to Germany Hossein Moussavian in a CNBC interview. They believed that sanctions wouldn’t be imposed – and even if they were, they wouldn’t work because oil prices would surge.

Strong Arm or Upper Hand: The Shale Revolution and US Geopolitics

When Iran continued to enrich uranium despite UN Security Council resolutions and sanctions on Iranian exports by the US and EU, it seems that this oil-rich OPEC nation, accustomed to practicing strong-arm tactics in an energy-fueled geopolitical landscape, failed to notice one pretty significant thing: Growing production of US shale resources was lessening America’s dependence…