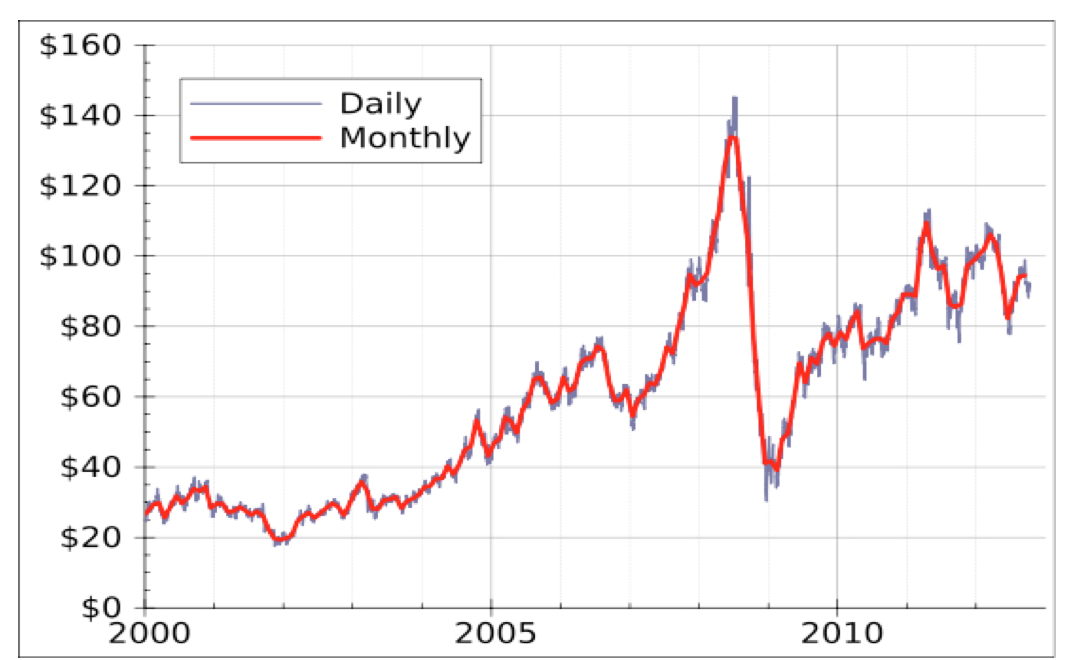

Historically, petroleum markets have been notoriously volatile. Natural gas prices even within the last decade have seen dramatic rises and falls. Oil prices have been known to surge at the slightest hint at a disruption in production.

But the US shale revolution has brought domestic oil and natural gas production to levels that we haven’t seen in decades. Oil production in Texas and North Dakota alone made up 83% of US production growth last year, and some estimate that West Texas oil production could soon rival Kuwait.