There’s no doubt that American energy is experiencing a shale revolution.

But is shale “the shot heard ‘round the world,” with global repercussions and international promise?

Do other countries have the same shale development potential that the US is experiencing? And even if they have the resources, do they have the technology to exploit the reserves, the infrastructure to transport and produce shale oil or natural gas, and the ability to export it?

The answers are mixed.

Russian Reserves Speak Volumes – But Loudly Enough?

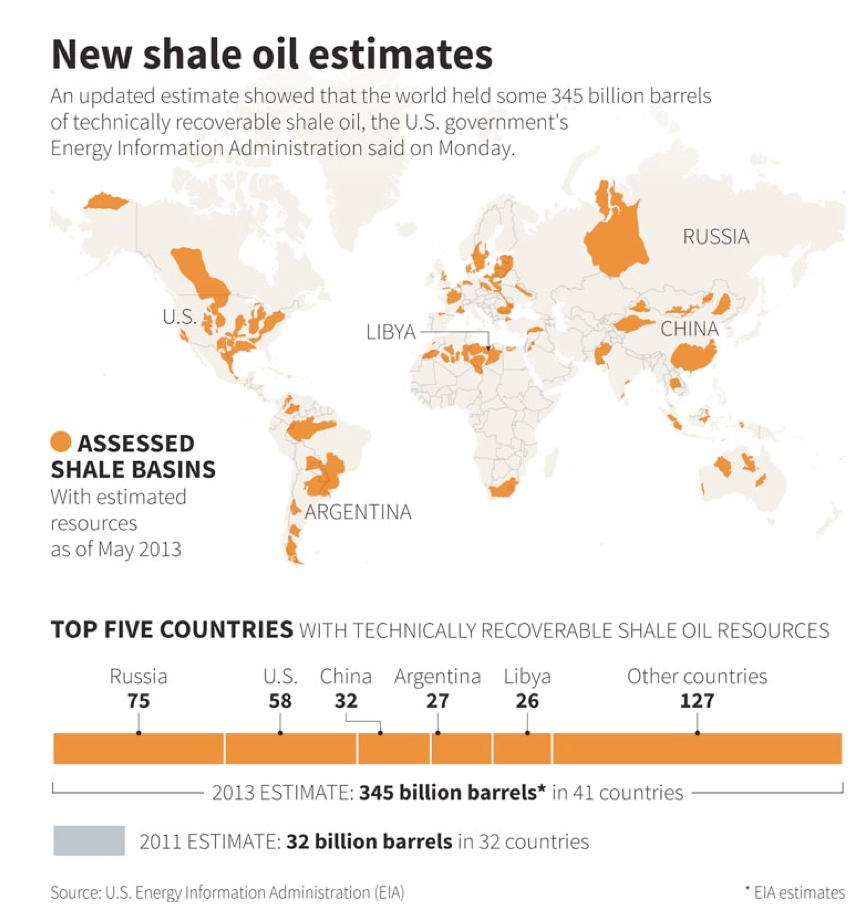

From a purely empirical standpoint – looking at reserves alone – Russia and China have the best odds of emulating the US success in recovering oil and natural gas resources from shale. Russia has more technically recoverable shale oil resources than we do – 75 billion barrels versus our 58 billion barrels, according to the Energy Information Administration – and China outranks us in terms of natural gas export potential.